The Logic of Lushness: Exploring Risk-taking in the El Yunque of the Mind

My recent trip to Puerto Rico took an unexpected primal turn in El Yunque, the US’s very own slice of Amazonia. Surrounded by a cheerful mob of fellow tourists, we all trudged along the same gloriously muddy track, our destination a natural water park featuring slick rock slides and a rope swing promising fleeting Tarzan glory. The local guides had issued a vital fashion advisory: wear shoes on their last legs – already bearing the scars of past adventures, ready for one last muddy harrah. Naturally, human nature prevailed, and the path became a stage for the subtle (and not-so-subtle) art of mud avoidance.

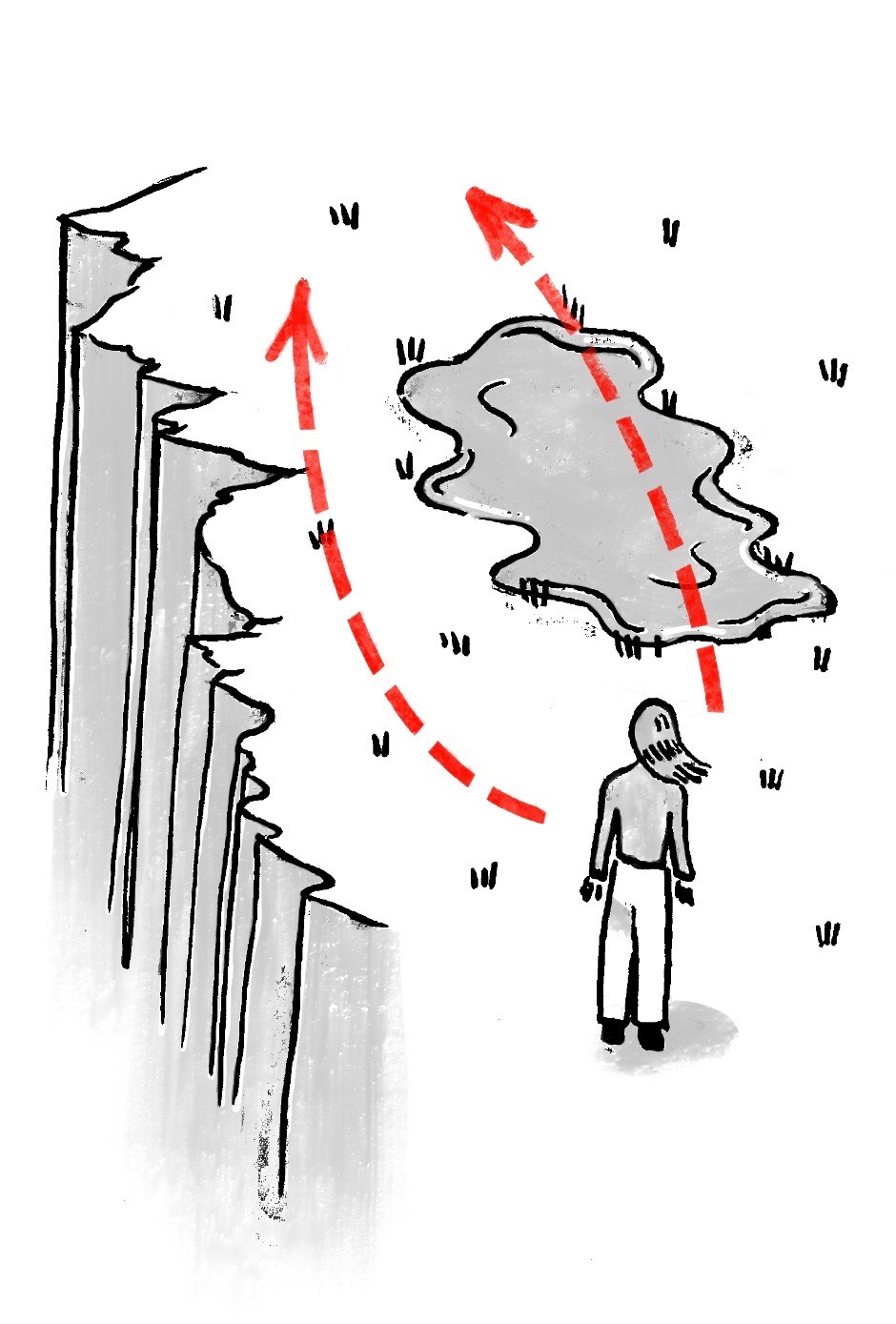

The widespread aversion to a bit of muck manifested in truly baffling ways. One particularly memorable instance involved a woman from another group who faced with a decidedly squishy mud puddle, opted instead to stroll along the exposed edge of what looked like a fifteen-foot cliff (as depicted in Figure 1). The logic here remained subtly elusive. Were her disintegrating foot coverings, their seams audibly protesting with each step, truly worth flirting with gravity? Did she possess an unwavering faith in her balance, or perhaps an underestimation of the laws of physics? The mind boggled at the risk-reward assessment that led to such a precarious maneuver.

The cliffside shoe-saving escapade, while extreme, merely highlights a universal truth: we humans are delightful and irrational, constantly weighing the ludicrous against the logical. From trusting suspiciously glowing street food to the plunge of online dating, risk is our constant companion. But how exactly do our wonderfully weird brains calculate these leaps of faith?

Well, according to Homo Economicus, a model of human behavior which assumes that individuals are rational, self-interested, and seek to maximize their utility, we should be able to make decisions based on logical calculations to achieve the best possible outcome. Amongst these Homo Economicus believing individuals are theories like the rational choice theory invented by Adam Smith which assumes that “every choice that is made is completed by first considering the costs, risks, and benefits of making that decision.” (“Rational Choice Theory”). Similarly, early neoclassical economists often implied that cost-benefit analysis happened very quickly, even instantaneously when making decisions. They modeled markets as if individuals could instantly process vast amounts of information and make optimal decisions. This assumption is unrealistic, as human cognition is limited, and decision-making takes time and effort.

On the other hand, Israeli-American psychologist Daniel Kahneman divides our thinking into two processes in his book Thinking Fast and Thinking Slow. System 1 and System 2 thinking. Kahneman defines system one as an automatic and quick system that operates with “little or no effort and no sense of voluntary control” (Kahneman). This can include what is “2+2?” or tasks like driving a car on an empty road. System 2 however is much more complex; Kanheman defines system 2 as a system that “allocates attention to the effortful mental activities that demand it” like doing your taxes or trying to learn how to play a musical instrument (Kahneman). System 1 and System 2 often work together. A great example of this comes with baking cake. As you read the recipe, understand the instructions, and mentally map out the steps your System 2 kicks in. It will continue to kick in as you plan for time and decipher measurements. Your system 1 kicks in as you whisk your eggs with the right technique. System 1 therefore may involve more biases to naturally incur, while system 2 is much more of a calculated choice (even if we don’t always get it right!). Moreso, behavioral economics says that our decisions (including risk-taking) are influenced by all kinds of biases from anchoring to overconfidence. That is why behavioral economics directly rejects Homo Economicus, with Duke University behavioral economist Dan Ariely saying that we are truly unable to be “perfectly rational” (“42 of Dan Ariely’s Best Quotes”).

So, what could some of these biases be in our scenario in the Puerto Rican rainforest? Well, the first one may be loss aversion. Loss aversion is defined as a cognitive bias where “the emotional impact of a loss is felt more intensely than the joy of an equivalent gain” (Pilat and Sekoul). In fact, previously referenced researcher Daniel Kahneman (alongside Amos Tversky) has noted that the idea of loss can be “twice” as powerful as an equivalent gain (Kahneman and Tversky 263). In this situation, the loss of traveling through the mud is dirty shoes and all of the discomfort and unpleasantness that comes with it. On the other hand, the gain of walking through the mud is the reduced risk of a fall or even faster travel time (taking the straight path vs going around). But you might question even despite loss aversion effects, why would the reduced risk of a fall not carry more weight given that it could potentially cause death or serious injury? That’s all up to the illusion of control.

The illusion of control is a cognitive bias where individuals believe they have more influence over events than is objectively true, particularly in situations involving chance or uncertainty. As Harvard University Psychologist Ellen Langer famously demonstrated in her pioneering work, people often act as if they can control random events, like lottery outcomes, simply by choosing their numbers. Langer allowed for some contestants to pick their lottery numbers while others were given random numbers. When allowed to sell their tickets back to the experimenter, those who had chosen their lottery numbers demanded significantly higher prices for their tickets than those who had been assigned numbers (Langer, 311).

In our El Yunque scenario, the woman might have overestimated her ability to navigate the cliff edge safely. She likely believed her balance, coordination, and attentiveness would prevent a fall. This overestimation is especially prevalent in tasks perceived as skill-based, even when they carry significant risks.

This illusion of control directly influences risk compensation. Risk compensation is the tendency to take greater risks when perceived safety increases. In this case, the woman likely felt a greater sense of safety walking on the cliff edge because she believed she had control over her balance and actions. This perceived control then allowed her to engage in greater risk. For instance, a study by Dr. Gerald Wilde at Queens University in Ontario on risk homeostasis theory (risk compensation’s code name) found that people adjust their behavior in response to subjectively perceived risk levels, often leading to increased risk-taking when safety measures are present (Wilde 209). For example, drivers who believe their cars are safer may drive more recklessly. In our scenario, the woman might have thought, “I’m a careful person, so I won’t fall,” leading her to disregard the objective danger of the cliff. This risk compensation is particularly dangerous when the perceived control is illusory, as it leads to a false sense of security. The combination of the illusion of control, and risk compensation, is a dangerous mix. Because the woman believed she had control over the situation (or so we may assume in this situation), she took a much larger risk than walking through the mud.

In the lush El Yunque, the allure of pristine footwear seemingly outweighed the primal instinct for self-preservation. The woman’s perilous choice highlights the potent cocktail of loss aversion, the illusion of control, and subsequent risk compensation that governs our often irrational decisions. While Homo Economicus might scoff, behavioral science reveals our messy reality: we’re less calculating machines and more emotional navigators, sometimes prioritizing spotless sneakers over solid ground. Perhaps next time, El Yunque should offer shoe covers – or maybe just a sign: “Mud is temporary, gravity is forever

Works Cited

“42 of Dan Ariely’s Best Quotes.” 42courses, www.42courses.com/blog/home/42-of-dan-arielys-best-quotes. Accessed 8 Apr. 2025.

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011.

Pilat, D., and K. Sekoul. “Loss Aversion.” The Decision Lab, 2021, https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/loss-aversion. Accessed 8 Apr. 2025.

Langer, Ellen J. “The Illusion of Control.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 32, no. 2, 1975, pp. 311–28. APA PsycNet, https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1975-25298-001. Accessed 8 Apr. 2025.

Mack, Lilila. “Two Paths to Choose From in El Yunque.” 8 Apr. 2025. Unpublished drawing.

Pilat, D., and K. Sekoul. “Loss Aversion.” The Decision Lab, 2021, https://thedecisionlab.com/biases/loss-aversion. Accessed 8 Apr. 2025.

“Rational Choice Theory in Social Work.” OnlineMSWPrograms.com, Feb. 2022, https://www.onlinemswprograms.com/social-work/theories/rational-choice-theory/.

Accessed 8 Apr. 2025.

Wilde, Gerald J. S. “The Theory of Risk Homeostasis: Implications for Safety and Health.” Risk Analysis, vol. 2, no. 4, 1982, pp. 209-25. Wiley Online Library, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1539-6924.1982.tb01384.x Accessed 8 Apr. 2025.